Verona

We had a day of exploring Verona today, getting lost a few times in this small city because of the windy streets, but we’re getting to know it.

I went out early and sat by the river, like yesterday, but this time decided to wander over to the Basilica of St. Zeno. It’s huge! I don’t know why I keep being surprised. Rick, Cathy and I came back later so that we could go inside. Some of the discoveries: different building design, painting by Raphael, alter piece by Montagna, and the most incredible bronze doors with plaques of different scenes.

From bikethecity.it: San Zeno Maggiore, or St. Zeno in English, is the patron saint of Verona. He was the 8th Bishop of Verona from 362 until his death in 380, known for founding Christianity in the city. He was respectfully nicknamed ‘il Vescovo Moro’, which translates as the Moor Bishop. This is due to his African origins as he was born in Mauritania.

Saint Zeno lived a simple life in austerity and was a well-educated man. He is considered the protector saint of fishermen because it is said that he used to fish in the river Adige.

The San Zeno Basilica holds his remains in the crypt under the main altar.

Here’s a bit of the church history from Wikipedia: “The current church was built on the site where at least five other religious buildings had previously been built. It seems that its origin is to be found in a church built on the tomb of San Zeno of Verona, who died between 372 and 380. The building was rebuilt at the beginning of the 9th century at the behest of Bishop Ratoldo and the King of Italy Pippin who judged it inappropriate for the body of the patron saint to rest in a poor church. The consecration took place on 8 December 806 while on 21 May of the following year the body of San Zeno was transferred to the crypt.”

Modifications/changes continued for centuries, but it feels cohesive even as you can see the particularly ancient areas. The art that I mentioned above was worth a lot of time and Cathy and I pondered the bronze doors for a good while. Our favorite was of one of the three artists, who cast himself doing the creating. He’s on the lower left side.

On the steps up to the altar, we saw a great example of the fossils that Krystal had told us about on our tour with her. She noted that the streets and sidewalks in a lot of Verona are made with marble, but it’s not really pure marble. Instead, it’s Verona marble, which you can tell because of all the fossils embedded in the stone.

Sharon, Cathy, Rick and I also went to the Duomo and did a quick tour. The most remarkable piece of the tour was seeing the 3rd and 4th century church through glass flooring under S. Elena’s church which itself started in the 9th century.

Then, we had the most amazing tour. Leaf had wanted to see the Biblioteca Capitolare, the oldest continually operating library in the world. And it was fantastic. He had a whole series of emails in goggle translated with the library to try to get us into an English tour – and it worked! The young woman who did the tour was incredibly knowledgeable and loved her work and sharing the stories.

Valeria, our guide, started by showing us the outside of St. Helen’s canonical church that a few of us had seen earlier when we toured the Duomo – only way to see the inside. In 1320 Dante Alighieri held his dissertation, the Quaestio de Aqua et Terra, in St. Helen’s canonical church. The church belonged to the same Chapter of Canons which was in charge of the Library. This event is remembered by an inscription on the external wall of the church. There was a statue designed to commemorate his 700th birthday.

We then moved to see many more mosaics from the Roman church that we’d first seen in S. Elena’s church. These continued through all of the buildings we were in – with sections of floor glassed, or flooring open to the designs below. Incredible. Valeria particularly liked 2 different mosaics. The one below had her name – a couple who donated to the churches gave enough to be able to put their name in the design.

This one’s first name meant dung – which could have had many meanings, bringing life, secure enough to carry off the name, and his design included 382 florins – which is how much he donated to put in a lot of mosaics.

When we were in this area, the site of the first church, she said speculation assumed that the library started in the 3rd or 4th century on this site. Here’s some information from the Biblioteca Capitolare’s website:

Originally, it was founded as a Scriptorium: a sort of writing laboratory, dedicated to the production of parchment books for the education and the spiritual training of the future clergymen.

The scribes, in charge of copying the books, belonged to the Schola majoris Ecclesiae, the Cathedral Chapter’s school (“Capitulus” is the Latin word for “Chapter”, from which the name “Capitolare” comes from). During the transitional centuries between the Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, marked by deep crisis, it was mainly churchmen who were given an education. Despite the political, social, demographic and economic decadence, they had the chance to receive and pass on the ancient classical culture.

One of those scribes, Ursicinus, left us the first written evidence of the Scriptorium’s existence. The book he copied, now known as Manuscript XXXVIII, contains the narration of the lives of St. Martin of Tours – written by Sulpicius Severus – and of St. Paul of Thebes, by St. Jerome. At the end of the last page, he added some data which were very unusual for the time: his own name, the place and the date. The date, written as “the Kalends of August in the year of consulate of Agapitus”, is identifiable as 1 August AD 517: a time when Verona was under the rule of Theodoric, King of the Ostrogoths.

The note, although very concise, is extremely important. In fact, it bears witness of a first form of cultural activity, organized for the book copying, back in the early 6th century. It is therefore likely that the first installation of the Scriptorium had been founded at least one century before. According to other scholars, its foundation might also be connected to the establishment of the first Basilica in the late 4th century.

Amongst the other treasures of the Capitolare there are also a few books even older than Ursicinus’: for example, Manuscript XXVIII, the oldest known copy of the “De Civitate Dei” (The City of God) by St. Augustine. It dates back to the early 5th century, and it is therefore contemporary with the author.

Valeria, our guide, had a group of 10 people who were in nerdeuphoria. Seriously cool. We were all riveted. She told us all of the above with a wry sense of humor and delight about what we were going to see and were seeing as we walked the cloister where the order of the Chapter still has members living and working in the library.

And the little room where priests or cannons were having a hard time following the rules spent time. Now, it’s where they keep their bikes:

And then into the library which had to be fully rebuilt after it was bombed by the Americans. Sigh. WWII.

The librarian Giuseppe Turrini had already removed the manuscripts and the most valuable printed books, and stored them in the rectory of Erbezzo – a small town on the nearby mountains. Other precious books had been previously hidden in a secret room inside the Cathedral. Those which were left, buried in rubble, were then partially retrieved and put back on the shelves after the hall’s reconstruction. They still show signs of the damage they underwent from the damages of the explosion. We could see this when she pointed them out.

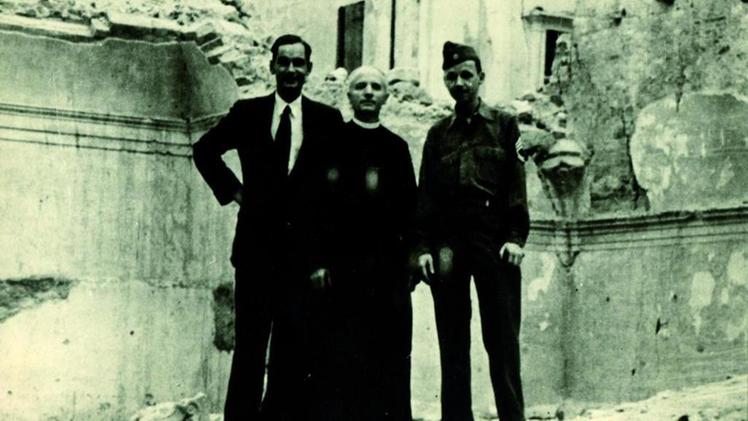

Wolfgang Hagemann, Giuseppe Turrini and Bernard Peebles in 1945.

Really – the story is amazing, so am putting the whole thing here, from L’Arena:“ A priest between two enemies who, on opposite fronts, had fought for a common goal: to save the Chapter Library from war. The image taken 70 years ago shows Monsignor Giuseppe Turrini, prefect of the Capitolare, between Wolfgang Hagemann and Bernard Peebles in the rubble of the library, in the uniform of a sergeant major of the US army, special department of Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives: the Monuments Men at whose feats the George Clooney film was dedicated. Hagemann and Peebles were eminent philologists, both had studied in Verona on the codes of the Capitolare. Enlisted on opposite fronts, they had found a way to get sent to Italy with the same concern: to save the Capitulary. Hagemann had arrived in Verona with ranks of officer and prestige: he had been Rommel’s personal interpreter, the desert fox. He placed himself at Turrini’s disposal and was invaluable: the monsignor, fearing the bombings which punctually arrived in January 1945 (destruction of the monumental Maffeian hall, 1,250 volumes and files lost) had transferred codes and manuscripts to the rectory of Erbezzo. He believed them to be safe, but Hagemann warned him instead of the danger: it was an area of anti-partisan operations and the Germans could set fire to the town (Vestena suffered this Nazi retaliation). Hagemann sent a trusted officer to Erbezzo, Fritz Weigle, who had also studied at the Capitulary in 1927, and he affixed a «befel» signed «Wolff/SS-Obergrappenführer u. General der Waffen-SS» which declared the KUNSTDENKMAL building: «Prohibited occupation and requisition», as translated for use by the fascist militias. In the last, dramatic period of hostilities, however, Hagemann intervened to advise the transfer of the codices to the Marciana Library in Venice and to other safer hiding places. Meanwhile, Peebles, who had already saved the archives of Philip V in Sicily, was going up the peninsula with the allied troops, recovering documents from 1713 that were used as wallpaper. Arrived in Verona with the first liberators, he rushed to the Capitolare: the photo shows him with the former enemy, rediscovered as a scholar and custodian of the cultural heritage.

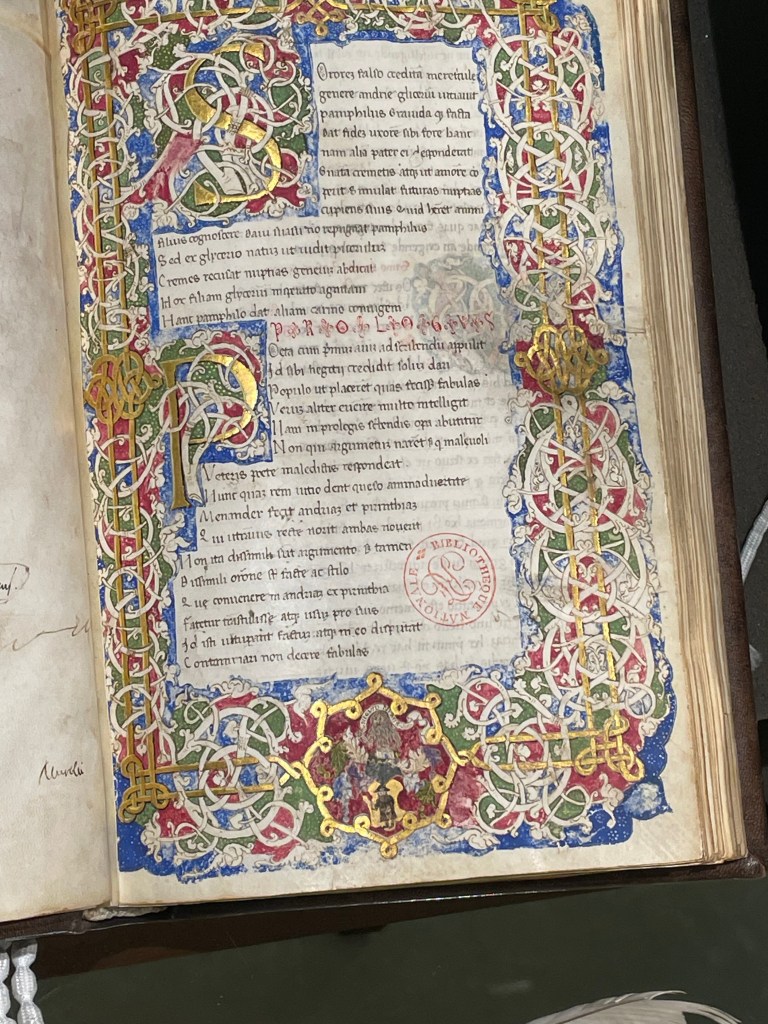

Then – the grand reveal – Valeria showed us several incredible examples of their collection. She washed her hands first and told us that the experts no longer used white gloves. They’d learned that the weave of the gloves could do damage and the lack of hand sensitivity with the barrier meant that damage could happen when turning the pages.

First she showed us books made with parchment – sheep for the big pages, lamb for the small pages. The yellower side was the outside where you could still see pores. It was incredibly durable and absorbed the ink really well. One skin held two pages, front and back:

The text below was taken by Napoleon after he left post invasion, each item was stamped as owned by France. They were able to get back about 2/3rds of the collection that he took away and felt lucky to get them. They have requested another specific book from their collection, but it’s been 25 years and they haven’t heard anything yet.

With the invention of the printing press, around 1450, the library got its first incunabula (early printed books, produced between 1450 and 1500). The one below was the Divine Comedy. Illustrated with incredible detail within the wooden blocks for the press – the big print on the written page is Dante’s words, the rest is commentary. Seriously.

Ok, I’m stopping, but man, it was amazing.